Sustainable Aviation Fuel Challenges

The Indispensable Role of SAF in Net-Zero

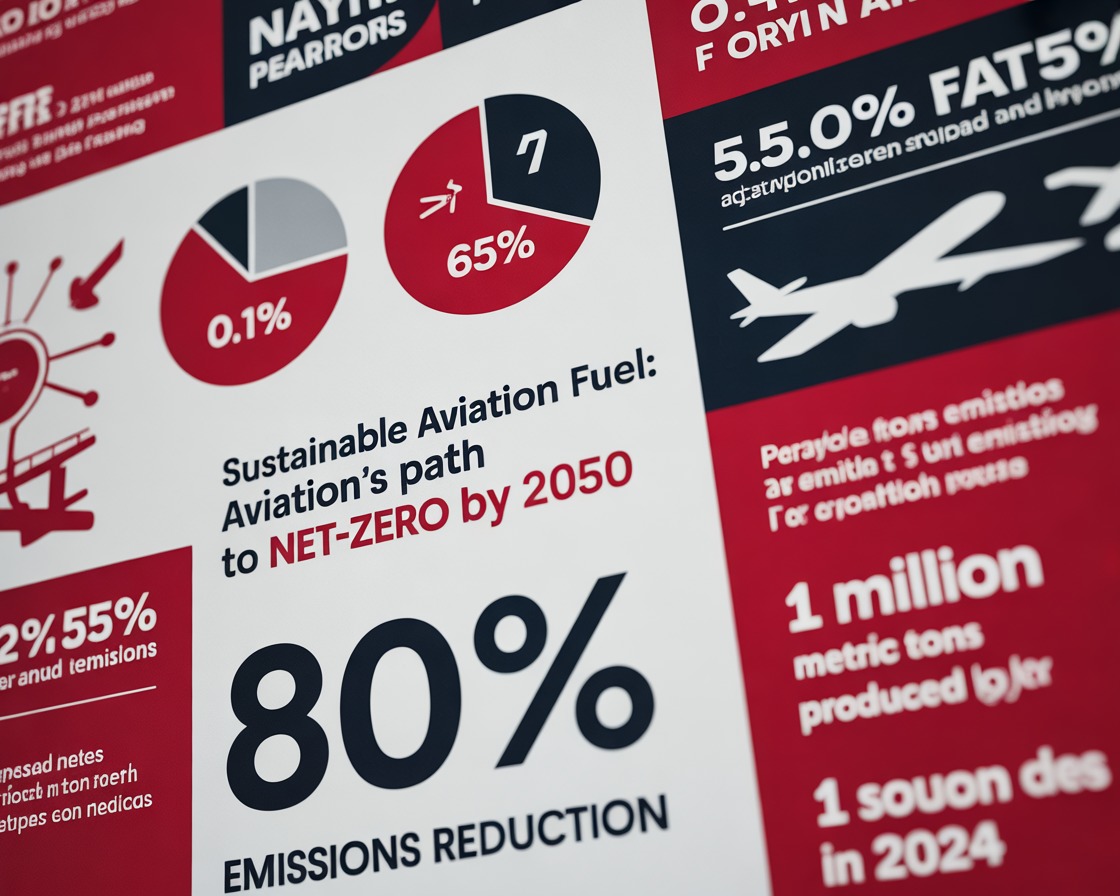

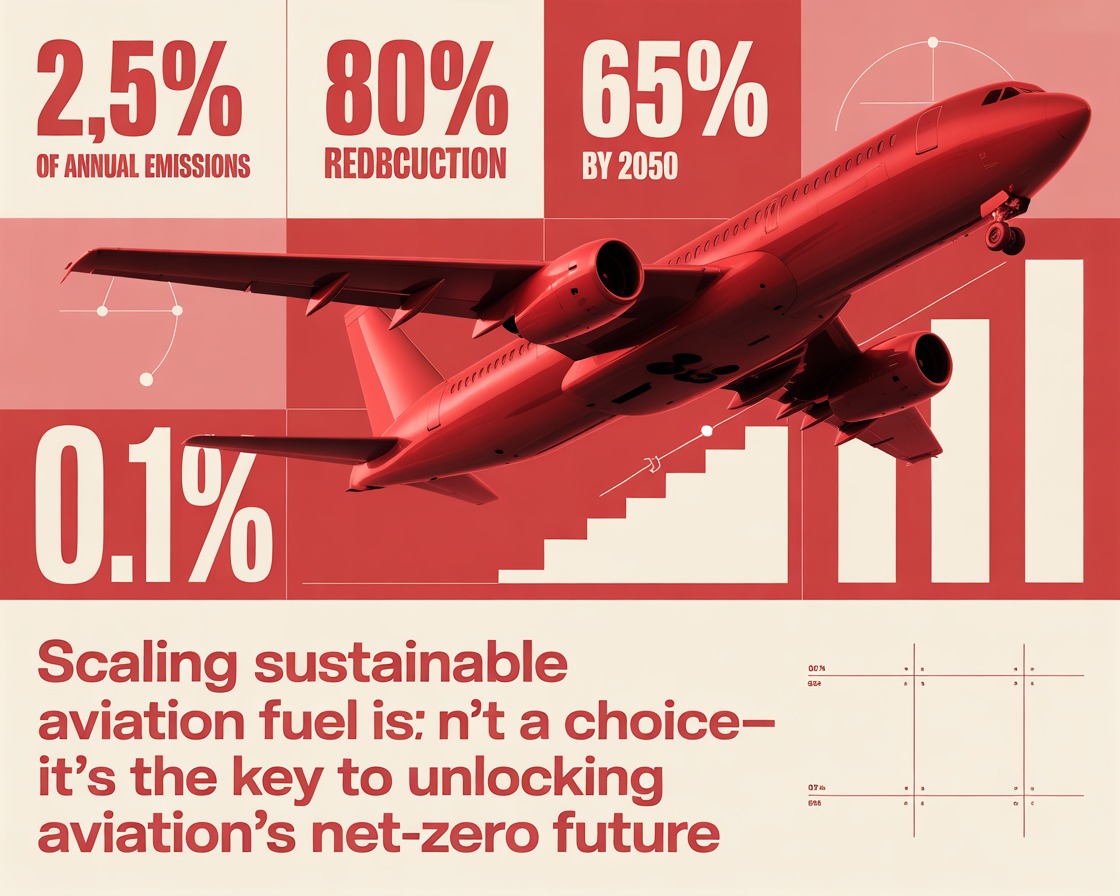

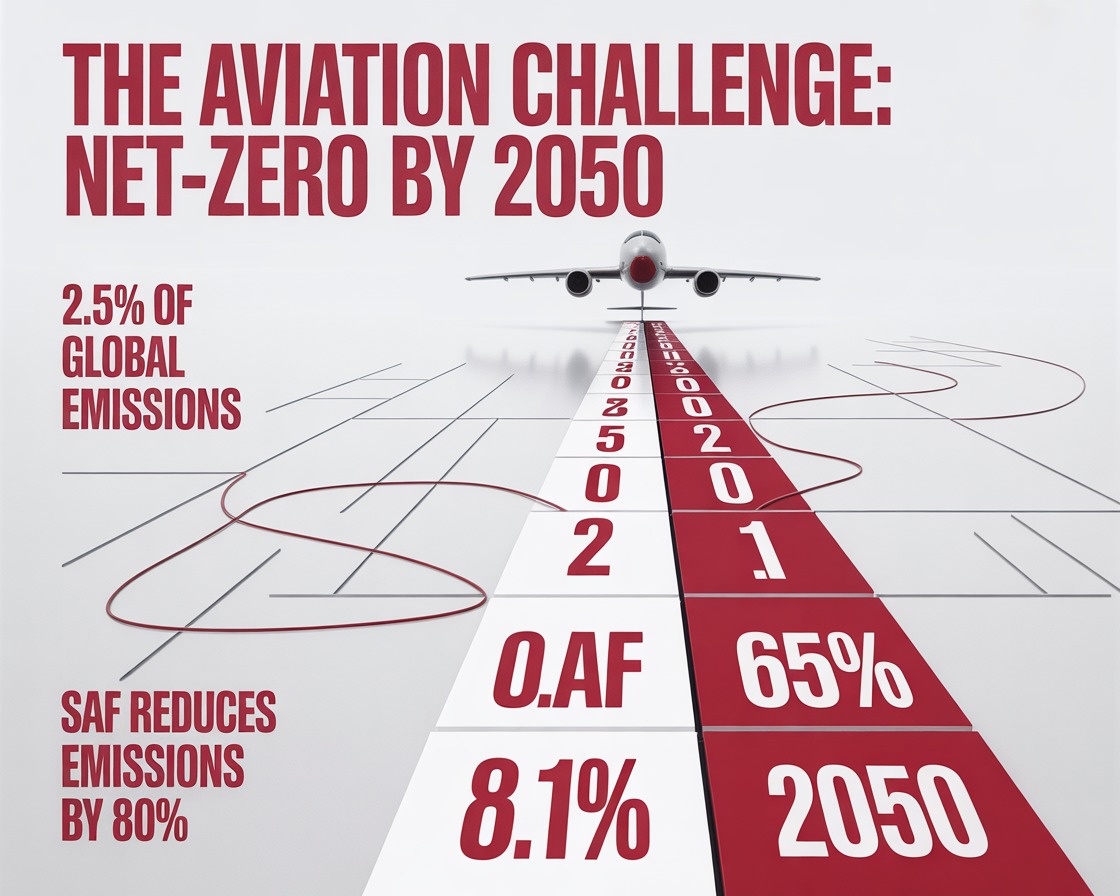

The global aviation sector, responsible for roughly 2.5% of annual global emissions, faces a formidable challenge: achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 [IATA, 2021 Resolution]. This ambitious target rests almost entirely on the shoulders of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF).

The global aviation sector, responsible for roughly 2.5% of annual global emissions, faces a formidable challenge: achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 [IATA, 2021 Resolution]. This ambitious target rests almost entirely on the shoulders of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF).

Despite its unequivocal promise, a significant gap persists between ambitious climate mandates and operational reality. While the industry needs Sustainable Aviation Fuel to constitute over 65% of its fuel mix by 2050, Sustainable Aviation Fuel Challenges currently accounts for less than 0.1% of global commercial jet fuel use [IATA, 2024 Market Data]. Global production capacity reached approximately 1 million metric tons in 2024 [ResourceWise, 2024 Report], marking impressive growth but still only covering a tiny fraction of demand.

Economic Barriers: High Cost and Investment Risk

The most immediate and profound constraint on Sustainable Aviation Fuel scaling is economic.

Prohibitive Cost Premium and Market Stalemate

SAF remains 2 to 5 times more expensive than conventional jet fuel [Argus Media, Price Analysis]. For airlines, where fuel already constitutes a staggering 20–30% of operating costs, this premium is prohibitive without regulatory intervention. In 2022, the average SAF price was estimated at around USD 2,400 per ton, roughly two and a half times the price of conventional jet fuel at the time [IATA, Economic Reports].

This cost differential has created a classic “chicken-and-egg” investment cycle: Producers need multibillion-dollar investments but cannot secure financing without long-term commitments; airlines cannot commit to multi-year contracts at current high prices.

Monetizing Carbon: The Role of Policy Intervention

Breaking this stalemate requires monetizing the carbon abatement value of SAF. Targeted policy mechanisms are essential:

- Blending Mandates: Regulatory requirements that create guaranteed demand, stabilizing the market.

- Tax Credits and Subsidies: Direct financial incentives, such as the Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Credit in the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), directly bridge the cost gap.

- Carbon Pricing Mechanisms: Mechanisms like the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) assign a financial cost to fossil emissions, making SAF more competitive.

Verification Challenges in Book & Claim Systems

“Book & Claim” systems are emerging to simplify logistics and financial transfer. A carrier purchases the certified carbon reduction credit (the Book), while the fuel is physically used by a different carrier near the production site (the Claim). While this facilitates investment, it heightens complexity in verification and auditing to prevent double-counting.

Supply Chain Bottleneck: Feedstocks and Logistics

HEFA Dominance and the Feedstock Competition Crisis

- HEFA Dominance: The Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids (HEFA) pathway dominates current SAF production, accounting for over 90% of global SAF in 2024 [CENA, SAF-Outlook 2024]. It relies heavily on limited waste streams like used cooking oil (UCO) and animal fats.

- The Competition Crisis: Global UCO and tallow supplies are highly constrained and already in demand from the road biofuel sector, driving up feedstock prices [SkyNRG, Market Outlook].

- Sustainability Risks (ILUC): Over-leveraging waste streams risks Indirect Land-Use Change (ILUC). Robust sustainability criteria and certification (like CORSIA or ISCC) are crucial to prevent this.

Scaling Technology: The Shift to Next-Generation Fuels

Achieving the massive scale required by 2050 demands pivoting investment to next-generation technologies.

1. Power-to-Liquid (PtL): The Zero-Emission Goal

PtL is the ultimate goal, offering a path to nearly zero-emission fuel not constrained by biomass.

- Process: Combines Green Hydrogen (from renewable electricity) with Captured (from industrial sources or direct air capture).

- The Investment Hurdle: Requires massive infrastructure investment in renewable energy generation, hydrogen electrolysis, and capture facilities.

2. Other Scalable Pathways: AtJ and BtL

- Alcohol-to-Jet (AtJ): Converts ethanol or isobutanol into jet fuel. AtJ has the potential to reduce life-cycle emissions by up to 94% compared with traditional jet fuel [US DOE, AFDC].

- Biomass-to-Liquid (BtL): Converts solid biomass (agricultural or forestry residues) into liquid fuel via the Fischer-Tropsch (FT) process.

Policy Frameworks: US vs. EU Case Studies

The lack of a unified global policy framework is a major impediment.

The EU: Driving Compliance Market Demand (ReFuelEU)

The EU’s ReFuelEU Aviation initiative sets mandatory blending obligations for fuel suppliers.

The US: Supply-Side Stimulation (IRA Tax Credits)

The US approach, driven by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), focuses on supply-side stimulation through tax credits.

- The SAF Credit: The IRA provides a direct tax credit of $1.25 to $1.75 per gallon to producers based on lifecycle emissions reductions [IRS, Notice 2024-74], immediately closing the price gap.

- Goal: The SAF Grand Challenge aims to scale production to 3 billion gallons per year by 2030.

Conclusion: The Long Runway to Commercial Reality

Sustainable Aviation Fuel is the indispensable core of aviation’s net-zero future. The challenges of high cost, HEFA dependency, and logistical fragmentation are structural and interconnected.

The long-term viability of global flight hinges on the collective, decisive action taken now to finance and accelerate next-generation technologies.

Clear and stable regulatory frameworks must be globally harmonized to provide the investment certainty required to transform this costly, complex product into an essential commercial reality.